Figure of interactivity. The grid scaffolds the abstract and arbitrary system of a mesh of regularly spaced lines, thus constructing a structural plane. This structural or structuralist aspect must be distinguished from what it is supposed to support—namely, the figuration that takes place within the structure. The grid is never fully adequate to the figure it supports, even though it is within the image, or rather superimposed upon it. From the standpoint of computing, the grid has the advantage of being regular, squared, and of a form close to a data-distribution diagram. It resembles what is called an “array” in programming. It is a form of visualization of the machine’s movement, as with the catalogue, except that here its level of abstraction allows for greater freedom in the construction of the interactive event.

One must depart here from the notion of the modernist grid in painting, self-present and self-sufficient, as repeatedly analyzed, contextualized, and deconstructed by Rosalind Krauss. Especially in the case of hypermedia—and above all in the case of interactivity—the grid is not a rational presence; it is not a window onto the world. It is not “logical”; it simply has a logic—its own—which it imposes upon its object. It distorts the image. This is the only true “danger” of the grid for interactivity: that its perfect symmetry be taken as the expression of a truth of computation.

Often, the figure of the grid appears in computing because it is easy to reproduce from a programming standpoint: since display, for example, most often operates according to a grid logic (axes x,y), designers of games, hypermedia products, and interactive objects constantly seek to provide quasi-direct access to this grid of manipulation. I can make my spacecraft go up and down, move it a few points to the left on the grid or a few points to the right. The grid is also frequently used in the sense of an array to organize an object of depth and complexity, which ultimately brings it back to the flatness of data distribution in computing. This is the case with QuickTimeVR (cf. weightless) and with the grid-maze proposed by games such as Doom or Quake (cf. map).

Yet the grid, as a figure of abstraction, is far more interesting not when it seeks to provide an adequate mode of visualization for a phenomenon, to be the appropriate image of that phenomenon, but rather when it allows no absolute adequacy between representation and object, and instead imposes itself as an abstraction of the latter. This is the strength of the grid, and what enables it to bring multiple phenomena—ontologically incommensurable—into communication on a single plane of abstraction. It then transforms everything upon which it is superimposed, even the mouse movements of the interactor, who suddenly sees an abstract grid projected onto their own body, upon which they pilot their “cursor.”

But it is also this second figure of the grid—its regularity—that must be overcome in interactivity, in order to allow more nuanced, more anamorphic grids to appear, which, through their superimposition, would enable another logic of interactivity to take shape.

cf. map, diagram, dispositif

bibliographie :

- Christine Bucci-Glucksmann, L'oeil cartographique de l'art, ed. Galilée, 1996

- Gilles Deleuze & Felix Guattari, Mille Plateaux, ed. de Minuit, 1980

- Hal Foster, ed.; Vision and Visuality, avec N. Bryson, J. Crary, M. Jay, R. Krauss, J. Rose; Dia Art Foundation, 1988

- Rosalind Krauss, The Optical Unconsciouss, MIT Press, 1993

- Rosalind Krauss et Yve-Alain Bois, informe : mode d'emploi, ed. Centre Georges Pompidou, 1996

illustration :

18h39

Serge Bilous, Fabien Lagny, Bruno Piacenza, CD-Rom, Flammarion, coll. Art & Essais., 1997.

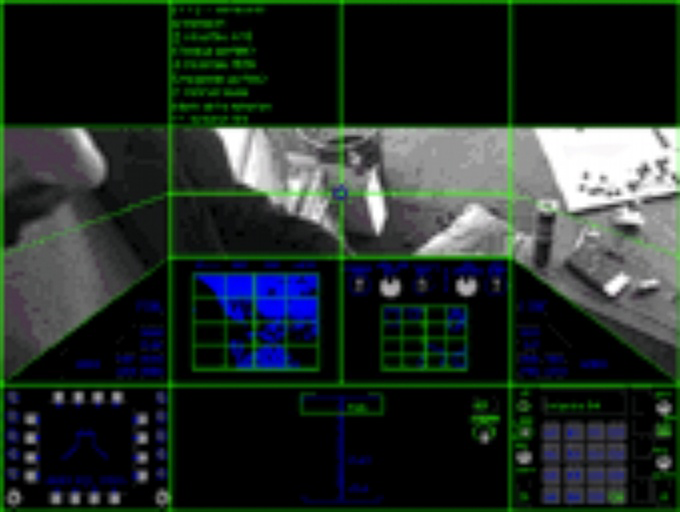

“The multimedia installation 18h39 invites the viewer to explore a photographic instant through a multitude of points of view. The title 18h39 corresponds to the time at which the scene shown on screen was photographed, but it also refers to 1839, the year photography was invented. Displayed on the computer screen is a black-and-white photograph, upon which a 4×4 grid is applied, implicitly referring to the ground grid used on archaeological excavation sites. The photographic document depicts an altercation between three individuals in an apartment furnished with a bookcase, a television, a coffee table, a refrigerator, a chair, and so on. The user attempts to understand the photographed scene by searching for clues within it.

An essential element of the interface, the grid offers sixteen possible zoom zones—predetermined advances in the ‘excavation’ of the image. When one clicks on one of the rectangles dividing the image, the click of a camera shutter can be heard. These advances proceed through successive levels of depth—specifically, three different levels. They are not simple enlargements of the initial image, but new photographic shots. At any moment, the visitor can return to the initial image.” (“Description of 18h39,” in Nov’Art, February 1997, Art 3000, p. 15).

In addition to this machine of abstraction represented by the grid, the dispositif of 18h39 also proposes a whole series of visualization machines. These machines range from the police composite sketch to the flight simulator, passing through 3D reconstruction, panoramic imagery, satellite photography, fingerprint analysis, and the hypermedia database. With each vision machine, the 18h39 dispositif offers the interactor a new experience of the initial image, a new point of view on that image. The grid is reconfigured, deterritorialized, and reterritorialized within a new figure of abstraction, as in the fingerprint analysis machine, which suggests that from the machine’s point of view, the fingerprint is also a grid—a distorted grid, or an anamorphic grid.

Dispositifs within the dispositif, 18h39 begins to multiply grids within the grid the further one “penetrates” into the image. The photographic image becomes a fractal image of bottomless penetration, an image of interactivity. The intercourse of interactivity—and here all terms are to be taken literally, especially given the nature of the image—never manages to find a satisfactory end, because no image provides the key image of the enigma, no image unveils the mystery as in a “laying bare” of the image. The grid is always on a plane of abstraction relative to the image, while at the same time being the very access to the image—that is, the experience of interactivity.

The grid is not above the image, below the image, inside or outside the image, but superimposed upon the image like a map. The image—its reference, its reality, its “truth”—recedes and is relegated to the background of a new image—image-grid, image-map—which continually constructs referrals, trajectories, paths, actions, interactions, and events within this new image. The hypermedia image thus becomes an abstract machine of modes of visualization of an image-trace, while simultaneously being, as in a hysterical investigation, the eternal reconstruction of the event. A kind of endless Columbo in which Andy has forgotten to turn off the machine.

On the basis of a hasty reading of Zeno’s paradox, one can nevertheless see in 18h39 the emergence of a kind of blurred image of an interactivity of effort, where the process of interaction is no longer production toward a product, but production of production—the production of the desire for interactivity.

Blade Runner

Ridley Scott, 1982.